Allen Ginsberg: Beat Poet, Counterculture Icon, Psychiatric Patient

An Excerpt from “Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness” by Stevan Weine’87

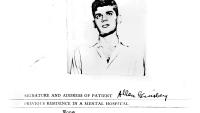

As a third-year VP&S student in 1986, Stevan Weine was thinking about specializing in psychiatry. “I was especially curious about literary views of madness,” he writes in the prologue to “Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness” (copyright 2023 Stevan M. Weine, Fordham University Press). Among the authors he read was Allen Ginsberg, Beat poet and counterculture icon who spent eight months as an inpatient at the New York State Psychiatric Institute from 1949 to 1950.

“I had questions, so I worked up the courage to write to Ginsberg, one of my heroes, and asked him how he reconciled the different views of madness in his art and life. Much to my surprise and delight, Ginsberg called me and asked to meet the very next day. He let me interview him and offered access to his archives and psychiatric records, as well as to his mother’s psychiatric records, which nobody outside the hospital had seen.”

Meetings over the course of several years followed, and Ginsberg encouraged Dr. Weine to pursue his research, which resulted in the book published this year. Ginsberg supported the project, Dr. Weine writes, because he wanted to address some key gaps and questions about his history with his mother and because he “was committed to leading others toward new ways of being human and to easing pain through his revolutionary poetry and social advocacy. Reckoning with mental illness and madness was a core component of this project.”

At a Lower East Side bookstore event earlier this year, Dr. Weine explained why the book was published 37 years after he first met Ginsberg. “The pandemic grounded me and gave me more time to write,” he said, but other reasons also explain the interval: He did not want to publish the book, which contains many family and personal secrets, until after Ginsberg died (1997), he needed to become a psychiatrist so he could better decipher the psychotherapy progress notes from Ginsberg’s NYSPI stay and his mother’s treatment at Pilgrim State Hospital on Long Island, and he needed to integrate psychiatric perspectives with the spiritual and artistic dimensions of what it meant for Ginsberg to walk with William Blake.

The book also became an opportunity to travel back in time to an earlier era of psychiatry, where the tragic history of lobotomy looms large. Even though Ginsberg authorized his mother’s prefrontal lobotomy in another New York state facility (Pilgrim State), and it caused him to feel tortured by guilt, the NYSPI records contain no mention of Ginsberg’s providing consent and little acknowledgement of his role as a family caregiver for his mother.

Dr. Weine describes a central question that the book tries to answer: “How did Ginsberg grab hold of the mental illness and madness in and around him and turn them into powerful poems that set off cultural explosions?” The poems he wrote helped to open minds and the culture about madness and mental illness in ways that made changes to humanize psychiatry not only possible but necessary.

— Bonita Eaton Enochs

The following excerpts from Dr. Weine’s book describe his discovery that Ginsberg authorized his mother’s lobotomy, reveal some of Ginsberg’s memories about his stay at NYSPI, and offer historical reflections on the use of lobotomies.

One afternoon in a reading room on Columbia University’s Morningside Heights campus in May 1986, I discovered an event of great emotional and moral weight, one not revealed in Allen’s “Kaddish for Naomi Ginsberg.” I am shocked because I think that in “Kaddish” Allen had committed to telling her entire tragic history, no matter how traumatic, painful, or embarrassing. At the time, I assumed that Allen’s poetry had to directly represent actual life experiences and be factually accurate. This assumption seemed consistent with the code he worked by, Jack Kerouac’s “Belief & Technique for Modern Prose: List of Essentials” from 1958, which pledged to deliver “the unspeakable visions of the individual.”

The event I discovered is documented on several pieces of paper kept in a folder of correspondences from 1947 in his personal archives at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library on the sixth floor of Columbia’s Butler Library. It concerned his mother’s lobotomy. When these documents turn up, I think this event from his personal life may be a secret. I have already read everything I could find on Allen Ginsberg and located no mention of it in his poems, essays, interviews, or in the critical and biographical writings. That an event so significant has remained largely unknown to his readers all these years, escaping the gaze of critics, scholars, and journalists, I find absolutely unbelievable.

______________________

We are sitting in Allen’s East Village apartment one late afternoon in September 1986, after he returns from his summer travels to Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Poland. I open my notebook, but Allen stops me before I can get off a single question: “Do you want to tell me what you saw first or would it be more interesting for you and your project if I didn’t know what you found in those files at PI to give my fresh answers at the moment without any forethought?”

After some nervous stammering, I say, “I want to first hear what you thought.”

“Yes. I was very conscious that my mother had been in the hospital, and here I was in the same spot. In the same kind of trouble. So that was a bit scary. Half my life was over, and I was getting into a state similar to hers. That’s a phrase in ‘Kaddish.’ And there is also in ‘Kaddish’ a recollection of a resolve. People disapproved of what I was doing and warned me that I had better watch out whether my sanity was a question. I better watch out, or it might get me in trouble. So I was quite aware of that.”

Allen speaks at length about the circumstances preceding his being at PI. He speaks of the experience of having visions, of living with a junky friend, Herbert Huncke, and of the spectacular car crash that led to his arrest and eventual hospitalization. His father and teachers criticized him harshly for hanging out with criminals. But these were his friends. In his and their defense, Allen points out that Huncke eventually became a published author. “My judgment was right, I think.” He adds, “More extreme, however, and more questionable was what was my relation to the visionary experiences I had with Blake, what was that and what had I concluded from it? What did I rationalize out of it, and was what I had rationalized out of it something that was unworkable, and impractical, and too metaphysical, and something that was getting me in trouble, because it was too absolutistic?”

Allen shares his memories of eight months at PI. He speaks of the mind games he played with his novice psychotherapists. Allen recalls once insisting to one of his therapists: “The walls were alive; that exists in some form of energy. That is deposited. You can call its presence everything its presence in that presence involves a certain amount of energy. But I was just banging my head against the wall with him. I didn’t want to get in trouble by having them consider me a complete nut. My aesthetic insistence was really not worth the practical trouble, because I think there was a question of whether I’d get out on weekends.”

Over several hours I listen and take it all in but I want to ask him about the lobotomy. If I don’t say it now, I may never get another chance. Already long into our conversation, I finally tell Allen, “I ran across a letter from Pilgrim State, dated November 1947.”

“To?”

“To yourself.”

“Where did you find it? In PI?”

“No, in your personal archives at Columbia.”

“What did it say?”

“Please be advised that your mother, Mrs. Naomi Ginsberg, was seen in consultation with the assistant director and it was decided that her mental condition is serious enough to warrant a prefrontal lobotomy.”

“Please be advised? November 1947? That was 1948?”

“November 1947.”

“Now that’s interesting. I would have guessed it to be in the 1950s.”

I thought this might happen, so I bring my handwritten notes to the interview. I pull them out, and we both look over the papers to confirm that I have it right. He then pauses in silence, looks down, and says, “Hmmm. That’s a very extreme thing.”

“What are you thinking?”

“I wonder to what extent there is a relation to my whole change of mind during that time, psychotic breakthrough, so to speak. Because I had to do the signing for that.”

“How did it make you feel?” (That’s either a hack psychiatric question or a reconfigured Dylan line. Perhaps both.)

“Well, I just had to cut my feelings out to do it. It had to be done. They said that, and I inquired further, somehow or another the decision for that fell on my head.”

Nearly 40 years earlier, Allen gave his written consent for the doctors at Pilgrim State Hospital to perform a prefrontal lobotomy on his mother. I had found a letter dated November 14, 1947, addressed to Allen Ginsberg, in Paterson, New Jersey, from Harry Worthing MD, senior director of Pilgrim State Hospital in West Brentwood, Long Island. Allen, just back from several months’ travels in Texas, Louisiana, and Dakar, was supposed to sign and return the letter by mail, which would forever change his mother’s life, and also his own. He was 21 years old.

“My mother was in a state of high pressure, high tension, high blood pressure, and a stroke was imminent. If she didn’t have a lobotomy, she would likely bash her head against the wall and likely have a stroke and die. She would explode literally. She was in such a state of anxiety, tension, and violent agitation that in order to save her life, they needed to give her a lobotomy to cut the affect. Is that possible?”

Our psychiatry professors at PI don’t teach us anything about lobotomies. It is regarded as the dark past of psychiatry, and the faculty is trying to impress upon us medical students that today psychiatry is just as scientific and professional as any other medical specialty. In medicine, memories of misadventures are short; hubristic efforts to cure, whatever the cost, are relegated to the long-gone days of ignorance. Modern psychiatry has long since left the lobotomy behind. If not for Allen and my discovering this letter, I would have, too.

To learn more, I visit the PI library and read their annual reports from the late 1940s and early 1950s describing the experiments being done with lobotomy. They tout them as achievements of a modern scientific psychiatry. Walter Freeman, the psychiatrist who promoted lobotomies and did more than 2,500 in 23 states, said the idea was to “apply a simple operation to as many patients as possible in order to get them out of the hospital.” What these papers didn’t state was that women were much more likely to be lobotomized, even though more men were institutionalized.

I read the original scientific articles by Dr. Worthing and the other leading lobotomists, which related their high hopes for psychosurgery in that bygone era. Historical reviews published far more recently show that not only were the promises of lobotomy not fulfilled but also that lobotomies were pursued in haste and without adequate regard for basic principles of science and ethics. By the 1960s, the consensus opinion was shifting against lobotomy. There were reports of serious adverse effects, negative media portrayals, and the new option of chlorpromazine (Thorazine). The more I learn about lobotomies, the more I understand why many in psychiatry would rather forget this part of its history. This wish to forget can also extend to some family members of the mentally ill who, from no fault of their own, signed up their loved ones for an irreversible procedure many would later regret.

A prefrontal lobotomy is a surgical procedure that was used by psychiatrists to treat schizophrenia and other types of mental illness. It involves making burr holes in both temples, then inserting a sharp, bladed instrument called a leucotome to make sweeping incisions in the frontal lobe, irreversibly severing the white-matter connections between the prefrontal cortex and other brain areas. At the time, some psychiatrists in state hospitals were using lobotomies widely. This was especially the case in New York state, which in the 1940s had one-fifth of the nation’s institutionalized mentally ill persons. Clinical experience and preliminary research suggested to these doctors that lobotomy might help with intractable mental illness, and the procedure became increasingly common, even though the benefits and risks had not been fully evaluated scientifically. The psychiatrists at Pilgrim State and many other institutions believed lobotomy was the hoped-for treatment that would revolutionize psychiatric care for the severely mentally ill. Before 1955, an estimated 30,000 lobotomies were performed in the United States. Naomi got caught in this wave of desperate measures to help empty the overflowing state mental hospitals.

Over the next several decades, the use of prefrontal lobotomy began to be regarded as harmful and ineffective. It became clearer that lobotomies caused a lack of emotional capacity and produced passivity and apathy. These personality changes were not effects of the original mental illness. It came to be widely held that it was a misuse or even abuse for those psychiatrists to have lobotomized so many people with mental illness.

Even in 1949, there were dissenters within mainstream psychiatry. Dr. Nolan Lewis, who had interviewed Allen at PI, asked in Newsweek whether lobotomy was merely a way to “make things more convenient for the people who have to nurse.” He objected to the “number of zombies” made by lobotomy and cautioned psychiatry to stop “before we dement too large a segment of the population.” Yet many of the psychiatrists of the day ignored such calls and got carried away by their own explanations, their research agendas, and their belief that they had found a cure for the most devastating of all mental illnesses.

______________________

Could Allen’s lengthy silence associated with the lobotomy have generated a longing to give a voice and a story to Naomi to make up for the irreversible harm done to her? Perhaps, but even the poems that mention lobotomy still present Naomi’s lobotomy as not fully utterable. “Howl,” his signal poem of protest, said little explicitly about Naomi’s mental illness and nothing about her lobotomy. But it did have the protagonist Carl Solomon showing up, “on the granite steps of the madhouse with the shaven heads and harlequin speech of suicide, demanding instantaneous lobotomy.” According to Dr. Walter Freeman, it was not uncommon for patients and their families to actually send letters requesting lobotomies, which, based on glowing media portrayals, they saw as a miraculous life-changing surgery.

“Kaddish,” on the other hand, seemed to say everything there was to say about Naomi’s mental illness and treatment. In contrast with “Howl,” which many fans know line by line, it is a poem not even hardcore devotees can recite. It is too sorrowful to keep in your heart or mind, too irregular to keep the rhythm, and at moments too painful to bring out of your throat without being reduced to tears. “Kaddish” is also full of painful mysteries; it mentions “a scar on her head, the lobotomy,” but does not further describe how or why Naomi got the lobotomy scar.

Upon learning about the lobotomy, I have a different response to one line in particular in “Kaddish.” After a thorough and exhaustive telling of Naomi’s life story, he asks her:

O mother / what have I left out

Even after reading this telltale line, it probably seldom occurs to most readers that Allen left anything out of this exhaustive poem. It never occurred to me until I learn about him giving consent. But is he saying right here that he did? Is he pleading with his mother to keep him honest? Naomi never did answer, not in a letter, poem, or in life. She never knew Allen signed consent, and she was gone before the poem was written. Her spirit might have said: You left out the fact it was you, my dear son, who signed the consent that put me through that awful operation. They cut me and put wires in my brain. You let them ruin me. My son, why didn’t you protect me?

In addition to Ginsberg’s works and his own interviews with Ginsberg, Dr. Weine used the following sources in these excerpts: “American Lobotomy: A Rhetorical History” by Jenell FreemanJohnson; a Canadian Medical Association Journal article on “(F) ailing Women in Psychiatry: Lessons from a Painful Past”; a Journal of Medical Ethics article on “Ethical Considerations of Psychosurgery: The Unhappy Legacy of the Pre-Frontal Lobotomy [with Commentary]”; “The Lobotomy Letters: The Making of American Psychosurgery” by Mical Raz; a New York State Archives article on “Mental Health in New York State, 1945-1998: A Historical Overview”; “The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders” by Richard Noll; and a Journal of Abnormal Psychology article on “Personality Changes Following Transorbital Lobotomy.”